You will probably be familiar with the concept of the ‘urban-rural divide’ in environmental policy – the idea that environmental action is imposed by city-based policymakers and activists onto rural communities who resent it.

This is an idea that has been at the heart of media coverange and political debate around recent backlash to environmental measures, notably the farmer-led protests that swept Europe ahead of the EU election.

And to some extent it speaks to a real issue. Many of the measures necessary to tackle the nature and climate crises, from ecological restoration to the creation of energy infrastructure, have to take place in the countryside. And many of the vocal and visible advocates for those measures are very much not from the countryside.

But is there actually a divide between how urban and rural populations think about these issues? This was the question Scottish Environment LINK sought to explore in our polling conducted by Diffley Partnership (which was mentioned in the last edition of this newsletter).

The way Diffley approached this was to create three distinct population samples who would be polled on the same questions. There was a standard, nationally representative sample with around 1000 participants. There was a rural sample of 700 participants drawn from rural postcodes. And there was a sample of 500 people living in the Highlands.

This approach allowed us to measure the attitudes of rural Scots compared to a national average. And we designed questions to deliberately see to what extent we would find a divide in attitudes, ranging from broad levels of concern over the environment to specific issues, such as farming and fishing, where we might expect to see distinct rural attitudes.

The full report is available on the LINK website, and includes both the polling and findings from rural focus groups. But I wanted to pull out one specific question.

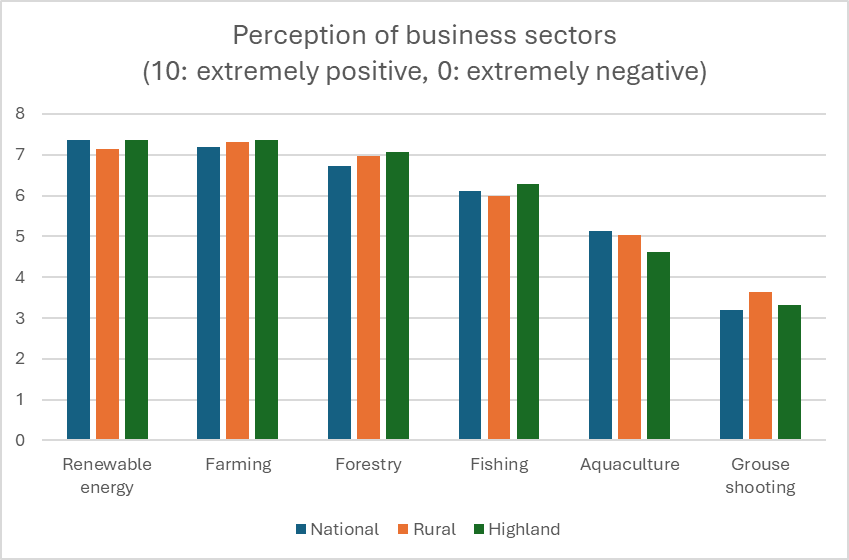

We asked participants to rank their perceptions of various prominent rural industries out of 10, with ‘10’ indicating they feel extremely positive, and 0 extremely negative.

There are two significant takeaways from this result.

The first is that the results from all 3 samples are clustered around very similar numbers. There are interesting variations (rural/Highland participants are marginally more positive about some sectors, but marginally more negative about aquaculture) but, considering sample size and the margin of error in any polling, I’m not sure these differences are at all significant. Instead, what we see is that the public perception of these industries is remarkably consistent across rural Scotland and Scotland as a whole.

The second point is what I see is a very likely link between perceptions of these sectors and their environmental impact. Renewable energy is viewed positively by all samples, while the sectors viewed least positively – aquaculture and grouse shooting – are those with the most obvious environmental concerns.

The results of the full poll echo this. The research finds that rural Scots feel deeply connected to the environment, are concerned about climate change and nature loss, and believe the government should act.

This doesn’t mean that rural and urban attitudes to environmental issues are the same: there are of course nuances, not least depths of knowledge and cultural heritage, that are hard to capture in an opinion poll. And there can certainly still be backlash if policies are percieved as being imposed on or insensitive to rural communities. Those concerns did come up in our focus groups.

But a ‘divide’? No – there is far more common ground here to build on.